As I mentioned in a previous post, data collected from these transcriptions are incorporated in the SERNEC database. There, anyone who is interested can access the results through a number of tools. I already mentioned the map tool, which lets the viewer search for all species found in a specific area. Here are a few others I’ve found interesting:

Location Search

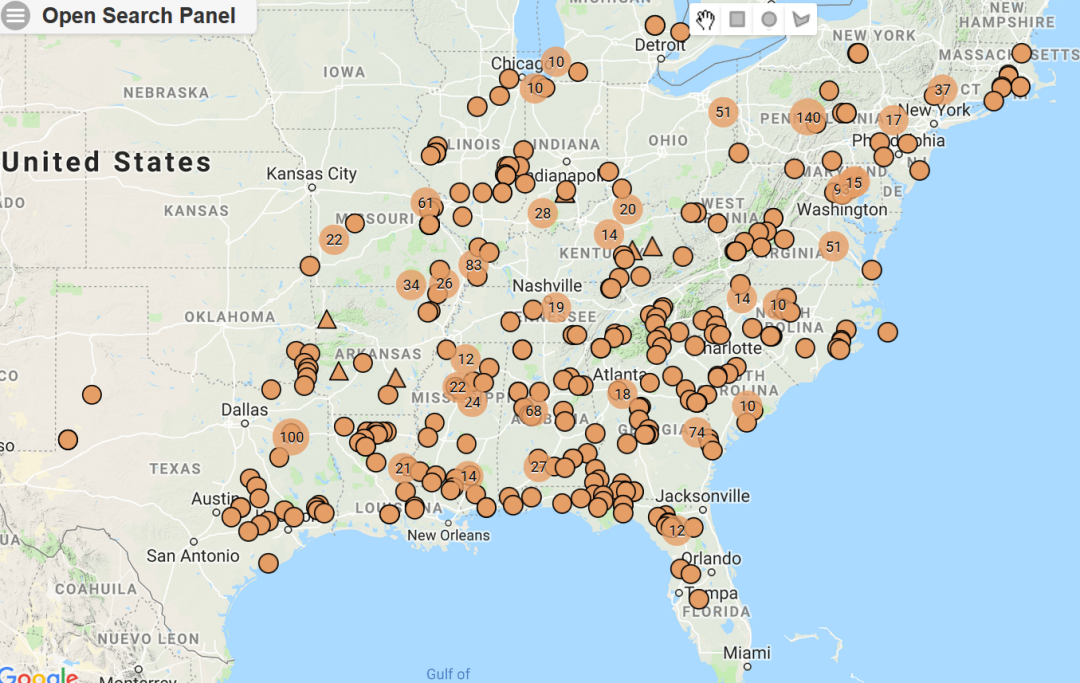

First, you can see all the locations where researchers observed a distinct species. I searched for Cornus florida, the flowering dogwood. As you can see in the image below, this species is widespread across the southeastern United States. Obviously, there are more dogwood trees than those listed below. Nonetheless, this tool provides a broad overview of the species’ range.

Image Search

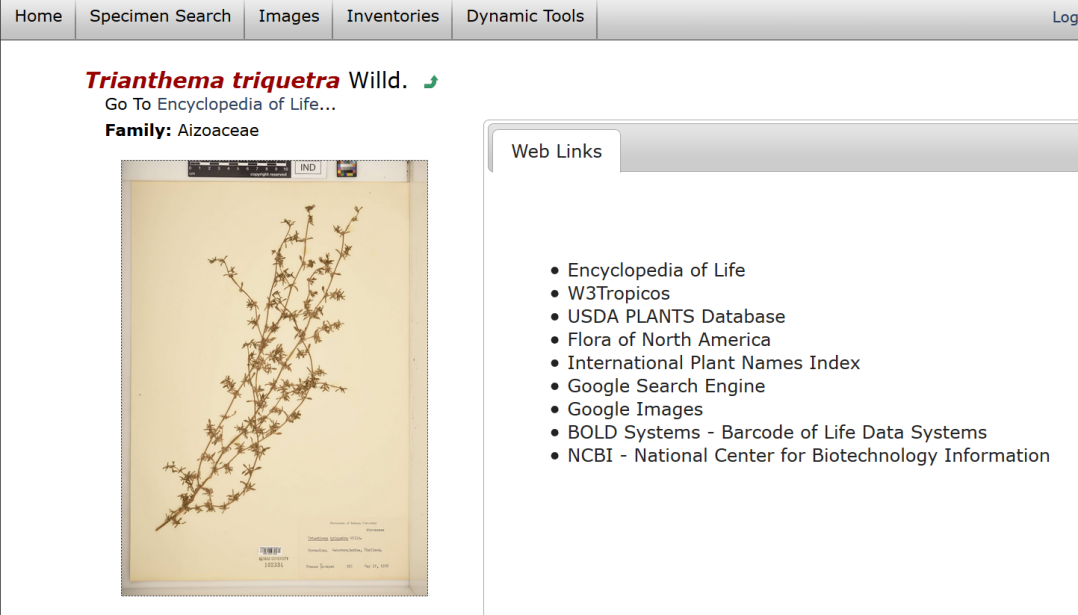

SERNEC also provides pictures of some of the species in their database. With only about 60 entries, this list is significantly shorter than their total list of species. They must choose not to upload images of everything. It’s a neat tool for testing your knowledge of scientific names, but I don’t see much utility outside of that. Here’s an example of one of their entries, which shows a picture of Trianthema triquetra.

(Side note—according to JSTOR, Trianthema triquetra is indigenous to Africa and parts of Asia. I wonder how it even ended up in this database? Perhaps they’re investigating it as an invasive?)

State Search

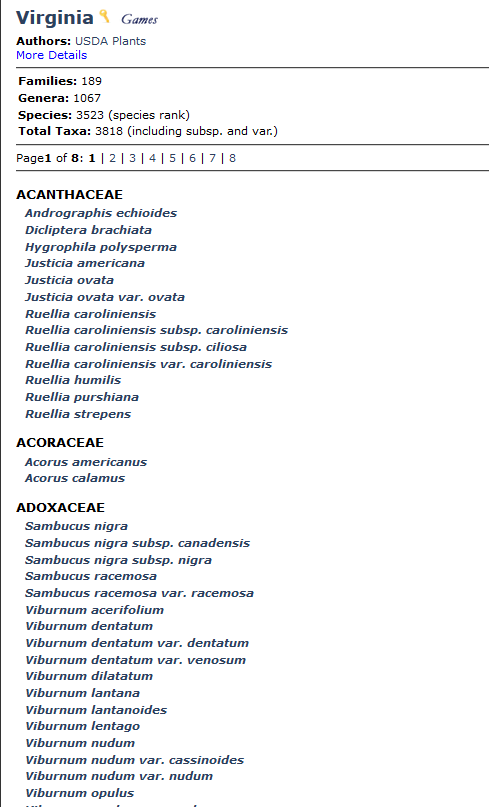

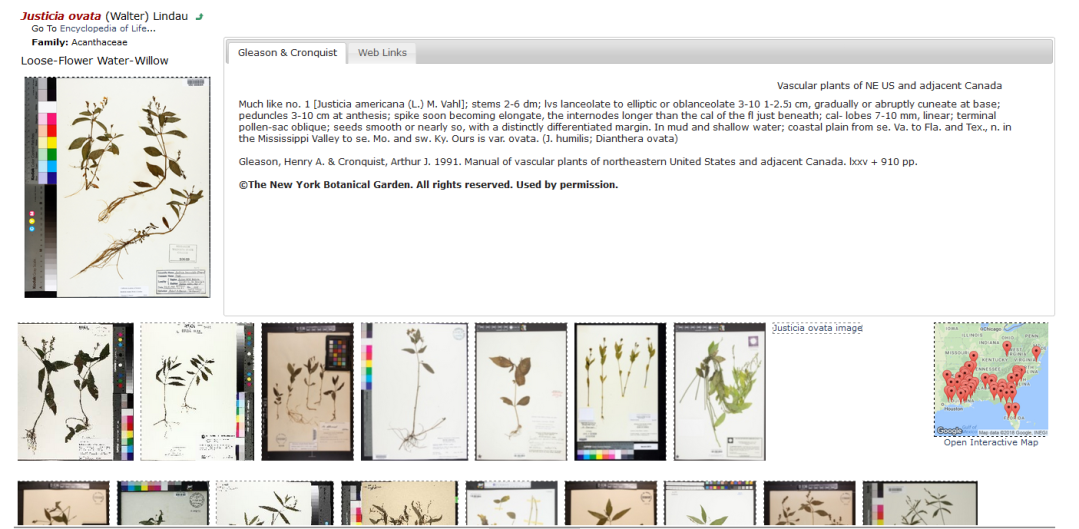

Finally, SERNEC allows you to see a list of all species recorded within a southeastern state. Within Virginia, their database includes 189 families, 1067 genera, and 3523 species. Clicking on any particular species takes you to a new page with additional images, information, and a distribution map. Below, you can see the page for the loose-flower water willow, Justicia ovata.